Owen Jones on the classification of abuse online#

What’s this?

This is summary of Wednesday 31st May’s Data Ethics Club discussion, where we spoke and wrote about a tweet from Owen Jones on the classification of abuse online referencing an article from the BBC investigating tweets sent to UK Members of Parliament. The summary was written by Jessica Woodgate, who tried to synthesise everyone’s contributions to this document and the discussion. “We” = “someone at Data Ethics Club”. Huw Day, Nina Di Cara and Natalie Thurlby helped with the final edit.

Firstly, we thought it might be helpful to briefly summarise the tool used in the investigation, how it was trained, and how it can be used. The BBC investigation used the Perspective AI tool, which “predicts the perceived impact a comment may have on a conversation”. The tool was trained on crowdsourced raters from Figure Eight, Appen and “internal platforms”, who labelled comments from online forums like Wikipedia and The New York Times. Raters tagged comments with attributes describing a range of emotional concepts. The main attribute is toxicity; other attributes include severe toxicity, identity attack, insult, profanity, threat, and sexually explicit. Not all attributes are available for all languages. Each comment in the training data was tagged by 3-10 raters, then post-processed to obtain labels corresponding to the ratio of raters who tagged a comment as toxic. For example, a comment would be labelled 0.6 for toxicity if 6 out of 10 raters tagged it as toxic.

In deployment, the tool predicts a toxicity measure for each inputted comment between 0% to 100%. Generally, comments below 50% aren’t labelled as toxic and don’t typically trigger an action unless they are flagged by a user. Toxicity scores reflect the likelihood of the comment being perceived as toxic. Perspective AI say that the tool’s intended uses are “to help moderators review comments, give real-time feedback to commentators, or allow readers to find interesting or productive comments”. Perspective AI advise against using the tool for fully automated moderation and character judgement.

Q1 The BBC News Article states: “Machine learning algorithms allow researchers and journalists to measure a phenomenon at a scale which would otherwise not be feasible with other methods.” Do you agree with this? Why/why not?#

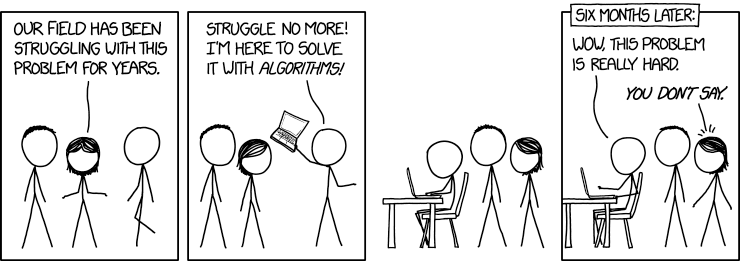

Machine learning (ML) seems to be often used as a catch all for any problem anyone has. There are a few problems with this. Firstly, the scale of a phenomenon which we are measuring with ML is unimportant if the sentiment assignment isn’t appropriate. If you aren’t measuring what you think you’re measuring, it doesn’t matter how big the area you’re looking at is, any conclusions you draw won’t be valid. Secondly, even if your sentiment assignment is sound and ML could in principle address the problem, the costs might be too high to make it worthwhile. Other methods might be more appropriate, for instance, there are lots of problems which can be addressed with normal statistics. There is a difference between the purpose of statistics and the purpose of ML, but this can get finicky and difficult to explain to other researchers – let along the public!

Concerning soundness of research, we found a few problems with the BBC News article. We thought the article was unclear on its evidence. The article is not specific about which tweets were analysed. Also, sources of original research are unclear - one graph showing an analysis of tweets was sourced “Twitter”, however we questioned if it should actually be sourced “Perspective AI”. The article does not show if the research was peer reviewed, who was involved in conducting the study, or if data scientists, political theorists, sociologists, and linguists were consulted. We noticed that the person who originally tweeted the study in 2022 (who Owen Jones retweeted) has not used Twitter again since, and the GitHub repo associated with the study has been taken down, despite it still being linked to on the BBC Data Unit’s main repo.

Q2 How can we decide if something is toxic? Who/what should be the ones to decide this?#

It seems unlikely that it will be possible to come up with a definition of “toxicity” which satisfies everyone; it is not something which can be measured objectively or scientifically. If humans can’t do this, we can’t blame a computer programme for not being able to do it either! To do our best despite conceptual muddiness means that the training data should be very carefully classified. This includes thinking about who is deciding what is toxic. For deciding any kind of label there should be a clear definition of what it means, with examples of what is and isn’t included. In many cases, classification will be a subjective decision, so the training data should accommodate for that.

We found some problems with Perspective AI’s classification of toxicity. Toxic comments are defined as those which are “rude, disrespectful or unreasonable” and “likely to make someone leave a conversation”. However, if there are racial slurs not being classified as toxic, and swearing is always toxic, it seems that perhaps the definition or classification method is missing something. We suggested that one way to understand ‘toxicity’ is that it erodes the standards of debate. For example, using swear words might erode standards of debate, if it indicates that people are just shouting at one another.

One of the reasons why problems with misclassification might arise is because the tool is not designed for fully automated evaluation and doesn’t understand context. Perspective AI maintains that for privacy reasons, they recommend avoiding the tool for character judgement, operating on isolated judgements rather than trying to make assumptions about the individual that made the comment. However, who is saying something and who they’re saying it to does make a difference in the toxicity of the comment. For example, a black person using the n-word is different to a white person using it, and MPs might also be a special case. Policing language without context of who is saying what can be difficult. Twitter often hides replies it thinks is offensive when very often the comments are not toxic in context, whilst other extremely harmful statements are allowed to slip through.

Accuracy with (mis)classification is distributed differently across different groups. There seems to be inconsistent moderation across different groups, for example abuse of trans people is famously poorly moderated on Twitter and this might be getting worse. Perspective AI have a known bias that they sometimes predict higher toxicity scores for comments with terms for more frequently targeted groups (e.g. “gay”, “black”, “Muslim”, “woman”) as those groups are overrepresented in toxic comments in the training data.

Another issue which may be behind misclassification of the tool is that for languages less seen in the targeted forums, labelled comments were translated from English into those lesser-seen languages using machine translation. This is an issue as cultural toxicity might look very different in different languages. Something labelled as toxic in an English comment might not have the same meaning when translated, and vice versa.

Sentiment drift can thus occur between different languages, and also within language through the passing of time. Language that was offensive several years ago might not be offensive anymore, and language which is seemingly innocent today may become offensive in the future (and vice versa). We need to think about how frequently language changes, and how moderation can reflect these changes. One approach might be to have an internet-wide dictionary which is versioned, but this could create barriers to already marginalised groups if they do not have fair input of knowledge. Perhaps grassroots moderation in distributed social networking like Mastodon is the best approach, as it allows people to make these choices within their own contexts.

Q3 Should the line of what counts as toxic be different if you’re someone in the public eye?#

We wondered if politicians are in roles in which you are subject to greater public scrutiny and should maybe expect a bit of adversity. In democratic states, having a role in politics opens you up to more intensive questioning and debate than may be otherwise expected. To improve democratic discourse, politicians should have some amount of openness to receiving negative feedback – within reason. The context of toxicity may be very space dependent, and we can look to the law (like the Equality Act) to provide a solid bottom line of what is acceptable.

Attendees#

Natalie Zelenka, Data Scientist, University of Bristol, NatalieZelenka, @NatZelenka

Nina Di Cara, Research Associate, University of Bristol, ninadicara, @ninadicara

Huw Day, PhDoer, University of Bristol, @disco_huw

Euan Bennet, Lecturer, University of Glasgow, @DrEuanBennet

Vanessa Hanschke, PhD Interactive AI, University of Bristol

Noshin Mohamed, Quality Assurance in Children’s Social Care, [@MohamedNoshin]

Amy Joint, Commissioning Manager, F1000, @AmyJointSci

Lucy Bowles, Data Scientist at Brandwatch, LinkedIn

Tseyi Okorodudu, Software Engineering Student, Federation University (Australia)

Joe Carver, Data Scientist at Brandwatch