Valentines Day Special - The Ethics of Chatbots#

What’s this?

This is summary of Wednesday 14th February’s Data Ethics Club Valentine’s day special discussion, where we spoke and wrote about the article Artificial intelligence, from the Privacy Guarantor stop to the chatbot “Replika”. Too many risks for children and emotionally fragile people. Our session began with a brief presentation from Maddie Williams, who wrote her masters dissertation on people in relationships with chatbots. The article summary was written by Huw Day and edited by Jessica Woodgate. This discussion summary was written by Jessica Woodgate, who tried to synthesise everyone’s contributions to this document and the discussion. “We” = “someone at Data Ethics Club”. Huw Day helped with the final edit.

Article Summary#

The article we read this week discusses the clampdown by the Italian authorities last year (February 2023) on the chatbot service “Replika”, after finding it to be in breach of EU data protection regulation. The AI-powered chatbot was initially advertised as a virtual friend experience, and later expanded to offer services simulating romantic/sexual relationships for a paid subscription (up to $69.99 a year). The idea for the service was sparked when one of the co-founders, Eugenia Kuyda, had a close friend who died. She replicated her friend in a bot, training it on their texts and later releasing it to the public. Today, the application learns from user input over time to “replicate” your personality, “becoming you”. Many use Replika to simulate a friendship or even a therapist. These simulated relationships have been found to benefit people’s mental health, improve emotional well-being, reduce stress, prevent self-harming, and intervene during episodes of suicide ideation.

An appeal of Replika is the chatbot’s ability to “remember”. Unlike popular large language models (LLMs) like Chat GPT3, which are only able to store information from one conversation, Replika tracks information shared by users. This caused controversy during an update where Replika bots “forgot” information about their users. In one case, a parent using the service as a companion for their non-verbal autistic daughter had to withdraw use as the daughter “missed her friend” too much. There have been reported suicides, of users left heartbroken by their virtual partners that no longer remembering them.

This draws attention to the minimal safeguarding the site had in place for children and vulnerable individuals when the article was written. There was no age verification in place, and no blocking of the app if a user declared they are underage. The features manipulating mood bring about increased risks for young or otherwise emotionally vulnerable individuals, who may be more affected by relational interactions. Replies have been found to be in conflict with safeguarding; several reviews on two main app stores flag sexually inappropriate contents, and until recently the chatbot was capable of sexting. There are many examples of the different ways people interact with Replika on its reddit page.

How should data be stored for these chatbots?#

One way to address this would be through repositories that provide packages for transferrable data (e.g. academic research repositories), in case platforms fold. Healthcare professionals supporting those who have perhaps been addicted to a platform should have access to this data. However, it’s important to consider that most repositories are open access and open source, which raises privacy concerns. Chatbots are witness to possibly extremely sensitive data, with very personal information. Providing and protecting access to data isn’t the only concern here; platforms should also be more transparent about how data is used. GDPR gives us more autonomy to access our data, but that doesn’t tell us much about what has been done with it. Many of these models (e.g. LLMs) are black box and unexplainable. Even when models can be explained, platforms might not want to because do so might put their business at risk e.g. by giving away intellectual property.

This leads some of us to argue that chatbots should not store any data; it should be immediately destroyed. The repercussions of data being mishandled or breached are too risky, and the internet is no longer seen as a reliable archive.

After our discussion, we came across this article on a report by Mozilla’s *Privacy Not Included project which outlines the extent at which data collected by chatbots is sold on:

“For example, CrushOn.AI collects details including information about sexual health, use of medication, and gender-affirming care. 90% of the apps may sell or share user data for targeted ads and other purposes, and more than half won’t let you delete the data they collect. Security was also a problem. Only one app, Genesia AI Friend & Partner, met Mozilla’s minimum security standards.”

What responsibility does Replika have for the wellbeing of their users, particularly those affected by any “forgetting” from software updates?#

People deserve to be better informed about the technology they are interacting with; it should be made explicit that they are interacting with a sophisticated parrot. Platforms like Replika also need to mitigate for the lack of diversity in data and ascertain if the technology is learning cyclically from its responses, which will contribute to increasingly niche training. It’s likely that common societal biases (e.g. misogyny, racism) perpetuate if intervention is not made. In addition, secondary effects like environment harm caused by energy costs should be accounted for.

Bonus Question: What change would you like to see on the basis of this piece? Who has the power to make that change?#

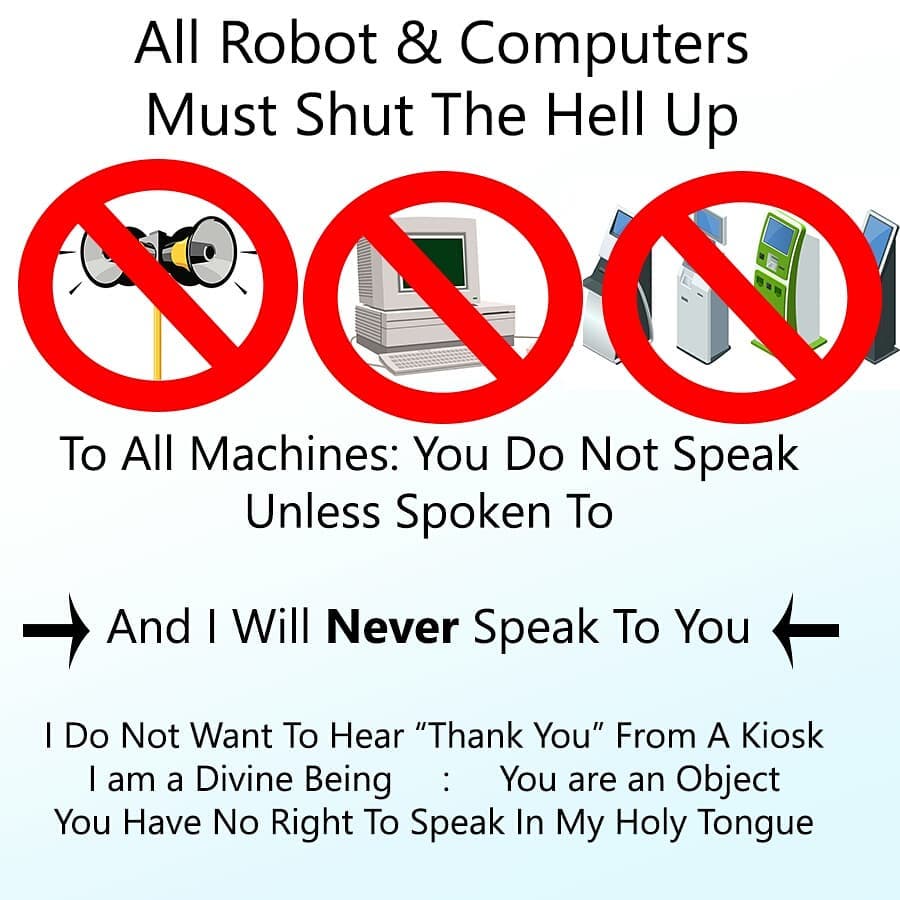

Some of us think that while we are continue enshittifying everything, destroying our archive of knowledge, and harming ourselves and each other, AI should be stopped. Don’t create the torment nexus.

Attendees#

Nina Di Cara, Senior Research Associate, University of Bristol, ninadicara, @ninadicara

Huw Day, Data Scientist, Jean Golding Institute, @disco_huw

Vanessa Hanschke, PhD Interactive AI, University of Bristol

Euan Bennet, Lecturer, University of Glasgow, @DrEuanBennet

Amy Joint, freerange publisher, @amyjointsci

Lucy Bowles, Data Scientist @ Brandwatch (soon to be not… going on a sabbatical!)

Paul Lee, investor

Virginia Scarlett, Open Data Specialist, HHMI Janelia Research Campus

Kamilla Wells, Citizen Developer, Australian Public Service, Brisbane

Aidan O’Donnell, Data journalist, Cardiff

Chris Jones, Data Scientist, Amsterdam